Some Reflections On Our First Year

Things we learned, discovered and realized in the first year of operating as Decentralized Agency—from creativity as skill, cognition as fallacy, and cooperativism as daily practice.

On the cusp of 2021, we (Marc Vermeeren and Bryan Wolff) launched a Why Paper that synthesized a six-month long conversation. In it, we laid out both the motivations behind, and purposely-loosely-defined aspirations of, our new collective.

Now, a year later, that conversation has continued under the banner of “Decentralized Agency.” As we look back, it turned out that the decentering of our own sense of agency—as in our capacity to act, and increasing this by letting others impact and decide over it—was as much an internal as external process. One that took place more outside of the collective, than within it.

Putting our intentions out there put us in touch with many other collectives, movements, companies and people. By giving them agency over us, they enabled our actions and catalyzed the continued development of our sense of self.

So before we try to put some words to how that sense evolved, we wanted to thank Social Service Club, New Models, Trust / Black Swan, Black Socialists in America, Index Space / Sanctu Compu, SPACE10, double up studio, Bram Krekels, Jan Gerrits, Tanita Klein, Ida and Simon, Doug Banks, Leïth Benkhedda, Philip Maughan and Andrea Provenzano, Joanna Pope, Johan Gerdin, Alice Grandoit, Binit Vasa, Cade, Daniël Sumarna, Robbert Maruanaija, Andrea van den Bos, Hollie Beever, Yasmin Dikkeboom and Emma Dietze.

There’d be no Decentralized Agency without them.

A special shoutout to Trust and Index Space for providing the platform to workshop the thoughts below.

For an overview of all those who inspired us with their writing, see our roundup of favorite links and articles from 2021.

Meshing professional identities

We won’t rehash our origin story (see the aforementioned Why Paper for that) but before 2021, we had only ever worked as creatives in advertising (for close to 10 years). Now we have worked for one year as creatives engaged in “critical theory” (for a lack of a better umbrella term), and are slowly getting more comfortable engaging with this space and level of discourse. A quote that bears repeating is one that has put us at ease ever since first reading it—back when one of us was joining Strelka Institute early 2020;

“The discipline of economics deals in all manner of things that do not exist outside the economics profession and its journals, conferences and models. And yet it is safely insulated from the realm of literary fiction, not least by the specialist language game it employs to insulate itself from the world (perhaps some enclaves survive postmodernity better than others). Lawyers, equally, traditionally see their role in terms of interpreting existing rules, but far less commonly in terms of inventing new ones or imaginatively recombining them. Meshing these professional identities with those of artists, activists, amateurs and dreamers would also mean weakening (or at least challenging) the rigidity of capitalist institutions, which are always partly imaginary.”

— from Economic Science Fiction by William Davies

Meshing ourselves with many others, we spent 2021 not only reading, but also designing speculative models and creative strategies across topics such as cooperative supermarkets, resource-distributing foundations, environmental footprints of the digital, and solidarity economies. The work itself has further helped us get comfortable and confident in the role we have to play—realizing it’s not so different from what we did before.

While the saying goes that good artists borrow and great artists steal, perhaps great creatives simply translate (and accredit their sources, such as that saying, which is attributed to Picasso, although he might’ve stolen it too). Creatives take complicated ideas and messages and turn them into something communicable, accessible, if not desirable. Most creatives today, whether that be writers, coders, designers, directors, or business managers, act to translate the ideas and messages of brands and products (if lucky enough to have that as their day job).

But it’s those very same skills that can help translate the ideas and messages of new systems, economies, forms of governance, equal ownership, common goods or overall better futures—especially if we want these to be able to overcome and overwhelm the status quo, with all its desirable distractions, temptations and pop-cultural allure in tow.

While there is a fair critique that cautions against the overdetermined role of “design,” there is also a danger in the imposter syndrome that already plagues many (including ourselves)—keeping us in a state of inertia and preventing a critical mass from engaging with those ideas we are in such desperate need of.

This is not about falling for solutionism, or ego-driven attempts at reinventing the wheel. This, to us, is about creating room for “interplay.” Not creating a “single event but rather an unfolding gradient of events,” to “forming conceptual pathways,” and helping to realize the “potential of what we already know and are now learning”:

“Transposing from a nominative to an active register, the intent of designing interplay is not to fix positions but to initiate interactivity—to disrupt loops and binaries. There may be no single new technology or magic bullet but rather a shift in the relationships between things. There may be no single event but rather an unfolding gradient of events. The designer is then temporarily manipulating the chemistries of assemblages and networks.”

— Keller Easterling, in Medium Design

“Knowledge is not an activity of mentally archiving information, but the recomposition and organization of information so as to invent conceptual pathways for the enablement of practical navigation.”

— Patricia Reed, in Blockchains and Cultural Padlocks

“Once more, competency does not demand omniscience, nor does it presume fantastic new technologies to suddenly align just right by deus ex machina. It demands, foremost, the realized potential of what we already know and are now learning.”

— Benjamin Bratton, in Revenge of the Real

Decentralizing Problems

Over the course of 2021, the word decentralization has become arguably overleveraged, and associated with Web3 and Blockchain to a fault. Nonetheless, we are proud to have it as part of our name, and continue to find inspiration in it; to decenter, from the single to the several. “Decentralization through the lens of human collaboration” but also through complexifying certain problems and expanding the scope of possible solutions and approaches.

Imagine for a second. Someone is drowning. You probably should throw them a life buoy, a direct form of relief. But it’d be ideal if there was also a team of lifeguards around, more of a systemic form of relief. You might also want to fix the boat’s balustrade so people are less likely to fall into the water in the future, sort of a direct form of prevention. And it’d also be wise to offer swimming lessons, making sure everyone on the boat can swim. A systemic change mitigating the issue even further.

These approaches are not either-or. From offering relief/adapting to preventing/mitigating, from direct to systemic changes, and from researching these in theory to developing them in practice—each combination offers a valid and needed approach. Which of these should take priority depends on the situation and who is answering that call, but broadly speaking this matrix has provided us a productive tool to think through.

The point is not to try and make sure every action covers every quadrant. Getting stuck on “nothing can be done unless everything can be done” is just another trap that leads back to stasis. Instead, by complexifying issues and becoming aware of the limits of certain solutions, we can engage with them more honestly. Rather than aiming for perfection, a band-aid is already improved when it acknowledges what it is not: a solution for the root cause (even though it is still a helpful relief).

Slavoj Žižek says as much in his interview in Fantastic Man issue 33 from last year:

“I'm a realist here. Everything that works is good and we should definitely do recycling, but recycling alone will not do it. Again, the Coke cans. So much waste goes into the production of a gallon of Coke, something like ten gallons of water for every gallon. Shouldn't we be questioning the waste in this production rather than simply figuring out what to do with the cans after we've consumed it?”

Not Everything ≠ Nothing

That initial feeling we described earlier when we brought up our problem matrix, as if nothing can be done unless everything is done, is a cognitive fallacy that we felt creeping up again and again.

Our brain (at least, “our” as in us two) constantly wants to break stuff down into absolutist dichotomies, even when in the midst of actively trying to escape them. It usually goes like this; We discover that something isn’t everything, and boom, the little instinct goes, then it must be nothing. Or something turns out to be not nothing, well, then it must be everything.

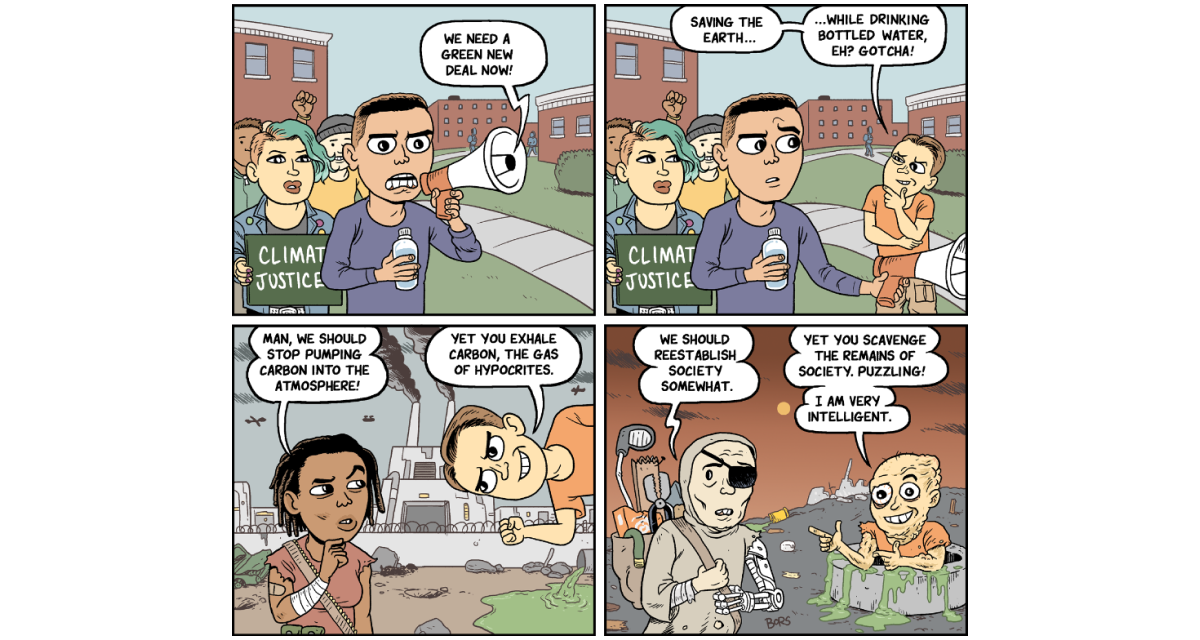

Take for example, individual consumer behavior. We know it’s not everything. It’s definitely not the fastest route to curbing our emissions at a planetary scale—no matter how much corporations would love to put that responsibility solely on us (all the while only 100 companies create 71% of global emissions, and despite a historical pause on consumer movement during the COVID lockdowns, carbon dioxide levels have continued to break records).

But when discovering that individual consumer behavior isn’t everything, the instinct wants to file it away as nothing. “Nothing we do matters.” Which of course is just as extreme and just as wrong as thinking that all that matters is consumer choices.

The same tendency has been fueling the sometimes unproductive debates around Web3’s energy requirements and carbon footprint—which is neither dismissible nor the key to net-zero. Neither nothing, nor everything. What to do when we realize Ethereum uses only 0.1% of global energy, yet, like almost all human activity, still aids a climate crisis that is death by a thousand cuts.

One thing we will do is continue to fight our own cognition. Things are rarely as absolute or simple as we our brains would like them to be.

Cooperative State of Mind

One final note. We have been educating ourselves on cooperative business models and the possibilities of solidarity economies (as being fought for in places such as Jackson, Mississippi, Chiapas, Mexico and Kurdistan). And with our fallacy-prone minds in mind, we are starting to see cooperativism as something that can extend to daily life as well (even if this isn’t doing everything).

The term cooperative is mostly known from businesses wherein every worker is also an equal owner, with equal say. But broadening the definition, it could be seen as creating space for people to impact those things that most impact them. As a worker, your workplace impacts you, thus a cooperative holds the space for workers to impact it in return (as equal co-owners).

Some feel like this is cumbersome, that it invites deliberation at every turn that gets in the way of optimized efficiency. Of course this is a feeling that capitalism thrives on, and why a bit of inefficiency and redundancy can’t hurt when trying to look for a pathway out of it.

As we enter our second year as a practice and collective, we hope to continue at a somewhat slow yet deliberate pace. One in which we have the room for ample deliberation, both between ourselves and with others, whether within the collective or outside of it. If you think we should hear from you, then we probably do, and so please don’t hesitate to reach out. Our aim is to always make space for others to impact us.

We hope that with this cooperative mindset we can owe up to our responsibilities, deliver on our abilities and provide for our needs, all the while avoiding false-dichotomies and inviting multiple voices. Here’s to meeting the universe halfway.

All bodies, including but not limited to human bodies, come to matter through the world’s iterative intra-activity — its performativity.

There are no singular causes. And there are no individual agents of change. Responsibility is not ours alone. And yet our responsibility is greater than it would be if it were ours alone. Responsibility entails an ongoing responsiveness to the entanglements of self and other, here and there, now and then.

We need to meet the universe halfway, to take responsibility for the role that we play in the world’s differential becoming.

— Karan Barad, in Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning

And I wouldn't be who I am today without the two of you, so likewise.